The Benefits of Engagement

Whereas dramatic efficiency gains and cost savings in the economy are rewarded through profits, promotions, stock price increases and market share, similar gains in government are rewarded with budget cuts, staff reductions, loss of resources and consolidation of programs. In this instance, incentives and rewards in the institution of government are the obverse of those in the market.1

— Jane E. Fountain, Building the Virtual State

It is a widely held truism that governments face difficulty implementing technology solutions, and that they generally manage IT projects very poorly.

It can be tempting to view this lack of technology acumen as a symptom of a larger disfunction. Governments are thought to be large, plodding organizations that do lots of things poorly technology management and implementation are but one of the many things that governments do not do well. But the challenges facing governments in how they use technology are quite specific. There are a handful of processes, all easily identifiable, that can work against the efficient adoption of technology by governments.

The annual budget process can provide a disincentive for new ideas and large efficiency gains by "punishing" innovative agencies with smaller allocations and reduced staff in the next budget cycle.

The procurement process—which can be lengthy, complex, and expensive—can turn away smaller or newer technology providers that might provide value to governments. These providers may simply lack the organizational endurance to get through the existing procurement process.

The civil service system can make it difficult to attract and retain employees with the latest technology skills, and budget support for staff training and skill development to keep up with changes in technology can be limited.

Changing any of these processes takes time and political will, and many of the defining qualities of these processes were put in place intentionally in the hope that they will lead to policy outcomes that are deemed desirable.2

As discussed in the prologue to this book, we now live in a time where people outside of government often have better tools to build things with and extract insights from government data than governments themselves do. These tools are more powerful, more plentiful, more flexible, and less expensive than many of the tools that government employees currently have at their disposal (often because of procurement or budget limitations).

Outside technology groups may have specialized skills and experience in building software or technology solutions that governments do not, or that those in the bureaucracy might face difficulty in acquiring. They are also typically unencumbered by political or administrative barriers that can sometimes prevent government employees from accessing new data or advancing new ideas.

The potential benefits of engaging and collaborating with outside technology groups seem clear to many people with firsthand experience with the limitations that governments face in developing new technology solutions. Respondents to a survey of current and former city government employees highlighted a range of potential benefits for governments that find ways to engage with their local technology communities:3

Fresh insights and perspectives.

Local data and tech advocates in the private sector provide the perspective that the city lacks. Progressive cities excel at building bridges between groups (community and business) that otherwise would operate in different spheres, extracting value from combining multiple experiences, skills and missions.

Access to talent that we don't have in government. There are so many skill sets and diverse perspectives on tech issues that we don't have currently in government. Working with outside groups allows us to tap into a wealth of knowledge and experience.

They help us imagine new tools/approaches we might not otherwise see, and can be a resource to get some of them built.

Respondents were also asked about the connection between outside engagement with local technology groups and government open data programs:

The city sees itself as the data producer - not necessarily as the app producer. Thus providing data at least up to point of delivery and no further ensures that were is plenty of scope for local civic tech to innovate.

In addition, respondents were asked about the connection between outside engagement efforts and other city innovation efforts:

...since we don't have an internal data analytics we are looking for ways to connect departments with researchers and data scientists to answer some of their big questions using data on our open data portal. There seems to be a lot of interest around this effort but we haven't got anything to stick yet.

There are real benefits for cities that develop strategies for engaging with their local technology community. Looking at a sample of case studies from cities that are doing this successfully shows that these benefits can be realized not only in large cities like Chicago and Philadelphia, but in smaller cities like Louisville, KY, and Syracuse, NY, as well.

Chicago: Using Predictive Analytics to Find Dirty Beaches

More than most other cities, Chicago is benefiting from the talents and skills of its local technology community by fostering deep connections with its members. The City's Chief Data Officer and other city officials are regular attendees at technology meetups, and are readily accessible to people in the community that have an interest in working on projects with civic benefits.

This regular, close proximity between city officials with access to and intimate knowledge of city data to members of the technology community with technology skills and a strong desire to improve their city has led to a number of successful projects.4

One of the more notable examples of how the City of Chicago is benefiting from the outside expertise in its local technology community is a project to build predictive models for identifying beaches that have heightened E.Coli bacteria levels.5 The city had previously developed its own predictive model for food safety violations internally,6 but this project was a departure from past experience. The series of predictive models developed to detect heightened E.Coli bacteria levels was developed in direct collaboration with outside volunteers, and the finished work was meant to be used inside the bureaucracy by the Chicago Park District.

While the preexisting model used by the Park District was error prone, in part due to its reliance on data collected by the Park District itself, the new predictive models developed with outside experts incorporated a wider range of data from many different sources:

While the prior model relied primarily on the Park District's immediate sensor data, the group tested a wide range of external data, including NOAA weather data, sunrise, sunset, and lunar phase data, and data on the status of regional locks and dams. Hyper-local weather information was also integrated into the model, from external data sources such as forecast.io and darksky.net.7

The experience helps to highlight one of the advantages that governments may realize by collaborating with outside experts on projects like this one. Those operating outside government may be less likely to be impeded in their work by organizational boundaries or political divisions. They may be more willing (and more able) to look farther afield for relevant data and experience that they can use to support such a project.

Louisville: Preventing Fires in Vacant Buildings

Like many other cities, the City of Louisville is working to find ways to better distribute smoke detectors that can help prevent loss of life when house fires occur.8

Of particular concern are fires that occur in vacant or abandoned buildings that can potentially spread to involve other nearby occupied structures. Finding ways to detect when fires occur in abandoned buildings more rapidly can help speed the response by emergency personnel and better ensure that such fires don't spill over into adjacent properties and put lives at risk.

The Louisville Fire Department, the Department of Community Services, and the City's Office of Performance Improvement and Innovation, as part of a related project, had already gathered data from across city agencies to look at where fires were occurring, whether they involved vacant structures, and whether those fires spread to involve adjacent properties. The city already had a pretty clear picture of where vacant structure fires were likely to occur, but they didn't have good information on what they could do about it given available resources.

The city decided to approach the local technology community for ideas. City officials asked for assistance in identifying ways that fires might be more easily detected in structures that were without electricity and that used low-cost components. In collaboration with a local technology lab,9 the city organized a hackathon to solicit ideas, build prototypes, and encourage broad experimentation.

City officials acknowledged that the local technology lab that spearheaded the event had access to resources that they did not that were essential to the ultimate success of the event:

LVL1 had the space, and, most importantly, the right network to bring people into the fold for the challenge. LVL1 brought together the supplies, advertising, and people for a successful competition that included four entries.10

The city, too, brought things to the table in the development of this event that made participation by members of the technology community interesting and attractive. Most importantly, it brought a difficult and complex problem to the table, the kind of problem that typically resonates with people that have data and technology skills. This problem was real, not theoretical, and impacted the city in which the people in the network of the local technology lab lived.

The city also provided access to experts inside of government, that provided context to problem and a better understanding of the data from the city:

We had a Major from the fire department, an IT expert from the Emergency Services department, and a fire protection company representative all participate as advisors and judges in the competition. It provided depth and understanding to the challenge that would have not been possible without them.

By approaching the local tech community as a full partner in helping to find solutions to the problem, and by bringing valuable assets like new data and access to experts to the table, Louisville has developed a model that it can use in the future to enlist the assistance and expertise of the local technology community on persistent city problems.

Philadelphia: Building a Mobile App for Transit Riders

The City of Philadelphia is well known for its embrace of open data and its close ties to its local technology community,11 but it was the transit authority in Philadelphia that led the city's first open data effort.

In 2011, the Southeastern Pennsylvania Regional Transportation Authority (SEPTA) began to experiment with the release of open data sets to the local technology community. Early in that year, SEPTA provided limited access to transit data to participants in a hackathon organized by a small fellowship team working with city government from Code for America. Later that year, at an event specifically focused on transit problems, SEPTA shared a wider array of data to a larger audience from the local technology community.12

Apps for SEPTA: Philadelphia, PA, October 2011

SEPTAs view of open data has evolved over time. Prior to formally embracing open data and encouraging outside developers to use its data, SEPTA resisted efforts by some in the local technology community to improve on what they saw as a suboptimal way of accessing transit schedule data. The creators of a mobile application called iSepta originally scraped schedule data from SEPTAs public website for their application. This early application gave transit riders a taste of what was possible if SEPTA opened up its data for outside developers to use, and gave SEPTA a sense of how interested outside developers were in building new apps, apps that would specifically benefit transit riders.

Originally developed in 2008, the creators of iSepta shut down their app in late 2014 because, as they noted in a final posting on the app website, "there are [now] other, better options available." These other options were almost all built with open data released by SEPTA after the iSepta app had been built and provided an object lesson in the power of the local technology community. (Incidentally, SEPTA launched a version of its own mobile app for Android users at almost the same time that the original iSepta app was shut down.13)

The approach taken by SEPTA in developing its own official transit app is instructive for other governments that want to collaborate with outside technologists.14 The official SEPTA app was never meant to replace existing transit apps that had been developed by the community—and by that time there were many—it was meant to complement them. By using open data and freely available APIs to encourage outside developers to try new things, SEPTA was given invaluable insights into the possibilities for its data.

What things would developers try and build? What new technologies were available for displaying and consuming transit data? What would work well? What wouldn't work well?

One way to view this approach is to think of it as a technique for outsourcing some of the risk inherent in developing new software applications and mobile apps. Using open data and direct engagement, SEPTA empowered outside developers to try new things and discover what was sustainable. Some apps were widely used,15 others were not and were eventually shut down.16

Having these kinds of insights prior to building an official app gave SEPTA a huge advantage in deciding what they wanted to build. It's also worth noting that the code for SEPTA's own official app was released as open source so that any transit developer—perhaps someone that had previously attended a hackathon and built a transit app of their own—can identify an issue or contribute an enhancement.17

Syracuse: Making Better Use of Road Data

Like other cities in the Snowbelt, Syracuse faces a constant challenge in maintaining its roads.

Brutal winters with record snowfalls lead to constant plowing and heavy use of road salt, which takes a toll on the condition of roads. A declining tax base, competing priorities, and lack of funding from the state and federal government exacerbate the challenge of repaving roads and keeping them in good condition.

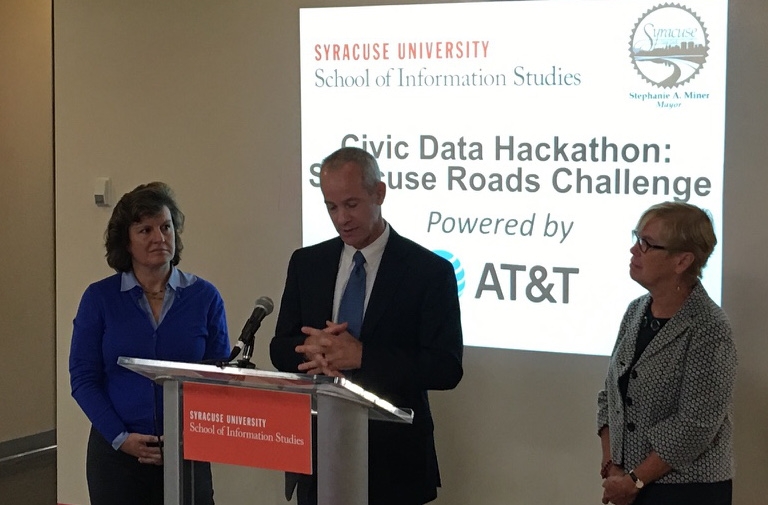

Syracuse Road Data Challenge Kickoff: Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY - September 2016

Syracuse has an abundance of existing road data, the product of work on other data-centric projects. The city is using truck-mounted cameras and inexpensive computers to map the location of potholes on all 388 miles of city streets, and is partnering with an outside group of data scientists at the University of Chicago to build analytic models for water infrastructure to help prioritize investment and repairs.

The city had been tacitly supportive of local volunteer efforts to use government data and technology for the last several years, and is now actively collaborating with local technology groups to encourage the use of road data to produce new insights.

Emulating the approach taken in Louisville, Syracuse is bringing existing city data and access to city experts to an event that will span several weeks and piggyback on an existing hackathon series that draws participants from across the Upstate New York Region.18 In advance of the hackathon, the city will hold a series of in-depth sessions (in partnership with the School of Information Studies at Syracuse University) where experts will help participants become more familiar with the data and address their questions.

Similar to Chicago's experience with outside developers to build a predictive model for beach quality, Syracuse is encouraging the use of a range of data sources from federal state and local sources to assist participants in their efforts.

Syracuse's efforts illustrate many of the techniques that governments can use to collaborate with their local technology community. It also demonstrates how these successful techniques can be reused by governments that are new to this type of engagement and that have smaller, more dispersed technology communities.

Summary

By finding ways to collaborate with a local technology community, governments can gain new insights and perspectives, and leverage special skills and tools that may be difficult to access inside of the bureaucracy, and harness them to find solutions to complex city problems.

Volunteer technologists and data scientists are less likely to be encumbered by political or administrative burdens that can make it more difficult to access data or advance new ideas inside government.

Encouraging outside developers to build new tools is a way for governments to outsource some of the risk and uncertainty inherent in developing new tools and services.

By sharing bureaucratic expertise, authority, and existing data with local technology organizations, governments can extend their networks farther into the local technology ecosystem than would otherwise be possible.

Piggybacking on existing technology events is an effective way to marshal the collective efforts of preexisting groups to work on new problems.

Endnotes

For example, almost every government has purchasing requirements for minority and women-owned businesses, and many have requirements that local companies receive preference over firms from another jurisdiction. The objective is to drive more government procurement dollars to minority and women-owned businesses and to local businesses that create local jobs and pay local taxes. Enacting these preferences is not inherently a bad thing, but using the procurement system as a vehicle for fostering outcomes can come at the cost of making the process more lengthy and complex for all applicants. This ideas is similar to the concept of tax compliance costs, credits and deductions intended to foster a specific outcome deemed desirable (e.g. charitable donations) may have the unintended effect of making the completion of tax forms more lengthy and more complex for all taxpayers.

To see a list of survey questions, see the Appendix.

For a list of some civic technology projects built in the City of Chicago, see https://chihacknight.org/projects.html. Note - not all of these projects were built in direct partnership with city government, but several notable projects were.

According to the National Fire Protection Association, a trade organization that develops model building codes, three of every five home fire deaths result from fires in homes with no smoke alarms or no working smoke alarms. http://www.nfpa.org/news-and-research/fire-statistics-and-reports/fire-statistics/fire-safety-equipment/smoke-alarms-in-us-home-fires

Several members of the city’s open data and innovation teams were previously active members in the city’s civic tech community.

It’s also worth noting that this approach stands in direct contrast to an approach taken by the City of Madison, WI on a pet registration application discussed in more detail in the Section 3.

For news coverage of one SEPTA app that was built by an outside developer that had wide usage see http://technical.ly/philly/2011/10/05/next-septa-developer-reed-lauber-launches-subway-bus-and-trolley-schedule-app/

For new coverage of a SEPTA app that was now widely used and eventually discontinued see http://technical.ly/philly/2013/03/19/mark-headd-septalking-shut-down/

SEPTAs open source code is hosted on Github at https://github.com/septadev

Last updated